|

I have been holding off on writing this blog, in normal Katie fashion- I have been waiting and intaking a lot of information. However, seeing posts from friends and family on my Facebook, and people still struggling with the meaning of “defunding the police” has me irritated and I am tired of waiting to find the right words. So, here it is plain and simple:

This fourth of July, I didn’t celebrate with fireworks, I wasn’t decked out head to toe in American flag garb, I was wearing black. I was in mourning for a country that only ever wants to focus on the positive things about America or the drama our media feeds us. In the middle of a pandemic, I put on my face mask, packed the sunscreen, hand sanitizer, and my water bottle, and headed to the park to meet with others for an anti-4th of July protest. When my roommates and I arrived at the park, there was no organizer to be found and no one seemed to know what was going on. Random volunteers were showing up with water, first aid supplies, and fliers about what to do if the police show up and the slogans we would be chanting. We casually wandered around and safely asked others if they knew what was happening, no one seemed to know, we were all just in the waiting game. So, more and more gathered and it got closer and closer to the time to start. At 2pm, starting time, 3 police officers showed up and started asking what we were doing there, who we were meeting, and what was happening- they too wanted to know who the organizers were. We didn’t know. So, the cops radioed back and forth with the station, “there are a lot of people in the park”, “no, they don’t know who the organizers are”, “yeah, yep, they are all just waiting with there signs”, No, not sure what else to do”. 5 Minutes passed and before we knew it, 12 police officers flooded the scene, breaking off in teams of two they started more questioning of the people gathered- though we still had no answers. As I scanned the park, it became clear to my roommates that the people cops were asking were white, they were young. The Police were not asking the first aid people or any of the folks passing out fliers- the people that could presumably know something. When the cops approached us, my roommate Laura spoke up asking them why THEY were here and what they knew about this event. The officer who had just got off of a facetime call with his son approached us and said “I’m officer _____, I have a background in deescalating hostage situations and distinguishing terrorist attacks. Although today I am only here to serve and protect, we as a task force respect your Freedom of Speech and are here to support you in any way.” It seemed that that officer wasn’t the only one supporting us, the whole march, 8 police officers walked with us and 6 police cars followed us as we chanted “defund the police”, “say their NAMES”, and “Nana AYUDAME” (Grandma help me, the last words a local Tucsonian spoke before being killed by the police force in a similar fashion to George Floyd. His story was not released until three months after the incident. Carlos Ingram-Lopez, PRESENTE!). This protest was more than a mourning of America, this was a BLM stance for change and anger for what has taken place. Throughout the whole march, it seemed the task force followed us. I started to feel guilty of my actions, embarrassed of what I was screaming to the friendly people around us, protecting us. But then, as we took our first break from the heat and drank water, I once again noticed who the police officers were interacting with and what their role was. When I say the WHOLE task force was looking out for us, I sincerely mean the majority of officers from TPD were “watching” this protest and as we looked around, it became less of an allyship and more of a watch party. The officer with a background in de-escalation and terrorist situations wasn’t there by accident. Also, even if he was, was it necessary to have the WHOLE police force at this gathering? Were we not paying them to be out protecting people, were there not “fireworks gone wrong” accidents or serious situations they needed to be in? This was a peaceful protest for change, not a riot or looting. Yet, our freedom of speech was met with fear and intimidation. The defunding of police, to me, means that we cut their funding. Tucson Police just RAISED their budget by 2 MILLION dollars. Which, will be used for new squad cars, paid leave, more guns, and more officers. It does not offer more training, background screening for who gets hired, or therapy for cops that have experienced trauma at work. I was 19 years old when I had a gun pulled on me by an officer in my small town of Mason City. I was being stopped for being at the park after hours and when I got out of the car to see what was happening, I was met with the barrel of a gun and a strict speech on never approaching the cop car. Something I was unaware of and didn’t think twice about being in a small town where my Grandma was neighbors with the former chief of police and we knew most of the officers in town. However, this incident was late at night, the man could not identify if I was a threat- could not tell my color of skin. He was scared. He was open about his fear and while searching my car for drugs and asking why I was at the park, told me about his three kids and how more than anything he prays every night to be able to return safely home to them. I am not disgusted by his fear, I am glad he was honest and I could tell he was sorry he escalated the situation. I would be fearful too with what see in the media and what evil I see in the world. But that’s why I am not an officer. Our officers need better training, less stress in the workplace, and more time to process what they go through. They need to not be victims of capitalism and treated with human dignity so that, that dignity can then be given to the citizens they protect. As I was walking down the street yelling “DEFUND TPD” and “JUSTICE FOR BREONNA TAYLOR”, I was reminded that the shame I was feeling and the guilt- was because of my white privilege and white response. Aside from that one incident with the police, I have never been afraid of an interaction with the police, or to ask an officer for directions. I have felt safe in their care because they, feel safe around me. However, my story does not account for George, Breonna, Carlos, and the COUNTLESS other BIPOC lives lost to police violence and victims of racial prejudice. Our police deserve and need proper training, they need support in their work, they do not need more weapons. Our officers are stressed because their presence is requested everywhere, their jobs are demanding. By reallocating funds and reimagining their jobs, we will relieve their stress and as a society push towards equal pay for equal work. Defunding the police, will reprimand and hold racist officers accountable for their actions. Jobs could be cut; many jobs, need to be cut or more evaluated. Not all cops are racist but many live in fear. Defunding the police starts to rethink and imagine our system. By defunding the police, we recognize that there is a problem in our leadership. Because although black on black crime is a valid acknowledgment, it misses the point. Our officers are our leaders and when our leaders show discrimination and disrespect, our community reflects these values. We cannot allow leaders to reinforce racism, we are doing that enough already.

0 Comments

I have always been a girl that loves her board games. Board games, card games, I LOVE games. I usually have a knack for winning and playing games is sometimes the only time my competitive side shows. Especially, if it’s a game I am used to winning, like Disney Scene- It or Rummikub. Then there are the games that I know I don’t win but still like to play. These are games like Stratego, Monopoly, and Risk. Risk was one of my favorites growing up, I used to love gathering around a table with my brother and all of our cousins around the holidays and spending HOURS on end prepping for world domination. I loved the intricate little soldiers, and cannons, the men on their horses. For those that haven’t played, the game is all about strategy, alliances and of course the end result and how you win is to concur the world. There are three types of militia of different point values and a map of the world colored by continent. Your job is to spread your army across every continent and take over the countries from other players on the board by rolling high numbers on dice. Playing this game enough times, I now have the perfect starting strategy: put all my troops in Australia first, then, as the game progresses, branch out from Australia into Egypt, over to south then central and north America, then spread across Asia and finish in Europe. Never EVER start in Europe. It is a tramping ground that is easily taken as there are no secure borders of protection. People can come and attack you from all sides of the map. Its best, to skirt on the sidelines, but everyone else is also trying for that strategy.

I usually last about halfway through a game. I am not the first person to be defeated, usually people leave me on the board because they know I am not a threat and they take the real competition out first. I usually make it through “alliance and treaty time” the time of the game where people build partnerships. “I ‘PROMISE’ not to go after you here if you help me take this piece of land from so- and – so over there”, or like in Monopoly, “I’ll give you this region if you can just help me or let me have this section here”. In a game where the ultimate goal is to be the last one on the map, its clear that getting there alone is hard. You don’t always have the support or militia you need. The tricky part of the game, however, is when these alliances start to break. It’s all fun in the beginning with people promising things to each other but halfway through it gets chaotic and tension arises. “HEY! You PROMISED I was safe here. What are you DOING!!!”, “SORRY, sorry, it’s a game, don’t freak out- you knew this wouldn’t last forever- You should have built up your militia and been ready!” Playing with my cousins, this is usually where I stop. We have a lot of competitive people in the family who despite this being “just a game” feelings get hurt and tension gets the best of us. The game quickly turns into- how fast can Katie destroy herself and exit the game and avoid the conflicts. All the girls are usually dominated at this point and are ready to play Barbies or House, something less violent. Its funny how a board game meant for children, can influence so much of life and enforce societies stereotypes and “values”. You may be wondering why I have spent most of one of my first blogs on Tucson, discussing a children’s game. It’s a valid question; I was curious as well when this game was on my mind the whole plane ride here. See, I was reading some of the pre-required readings on the plane (that I failed to read over the summer) and this game, kept coming back to my memories. For the next year, I have committed to being a Tucson Borderlands YAV. I knew coming in that a lot of the learning that I would have to do with life and culture along America’s “border”. A lot of the articles we were supposed to be reading, dealt with history of the border and how colonization happened very quickly and all at once. One article in particular, “Tohono O’odham Nation- History and Culture”, did a very good job in summarizing how abruptly a people can become displaced from their land and culture without so much as a warning or conversation. Like when you are sneaking your troops around the borders in Risk, instead of facing the conflict in Europe head on and in the open. The article tells a quick recap of how the indigenous people (Tohono O’odham) have lived on the land we Americans now consider the boarder for years before it was such. As colonization started happening, the people were promised not to have to worry, they wouldn’t have to change, they would be given special rights and license to maintain their “rights” as citizens. However, as time passed, the line was drawn and the promises made became blurred. Much like in the children’s game, it is hard to keep hold of promises when things are constantly developing. The world around us is always changing and more structure needed to be in place, the special identifications for the Tohono O’odham people eventually no longer mattered. Due to national security, our boarders had to be enforced so “outsiders” didn’t become a problem. The “middleman” had to be cut to assure the “enemy” didn’t stand a chance. If it helps to think of things outside of a “game” perspective for those that didn’t spend their holidays plotting domination, reading the article I also starting thinking of the well known and taught Native American peoples history and the struggles there with colonization. Here I was again, reading examples of other peoples being pushed out of their home, their heritage ripped away by newcomers who pushed for the “betterment of society”. Why do we find it necessary to teach our children about war? Why do we feel the need to establish competitive behavior, violence, mistrust, and strategic sneakery in our youth? Does learning how to “build and maintain an army” have to start so young? Let’s also note but not get into right now the gender roles displayed on who has the power and patience to maintain their armies. Reading these articles, I started to wonder why I saw the game as fun. I always lose interest and know what’s coming in the middle. Why do I play in the first place? The game continues to teach me that developing a strategy, maintaining borders, building alliances, and communication are important. It’s the key to winning the game. However, the untold and unnoticed lesson that we are also instilling is that it’s okay to break those alliances, hurt feelings, and break the trust, for the well being that this is just a game. The innocent bystanders aren’t your friends, neighbors, or innocent people. They are pieces of plastic, alien- like figurines, not human beings. In order to “win” and be the best you can be, you must be able to step on other people’s shoulders and make your way. I find it eerie how my brain can link an article to a children’s game and my brain can draw so many comparisons. I find it scary that I can see where so many life lessons and social structures get formed, without ever taking a second to realize what’s happening. I find it horrifying how fast we can turn on people and focus on the “betterment” of the game, of the country, of the world. Pushing people’s feelings to the side and getting wrapped up in “end goals”.

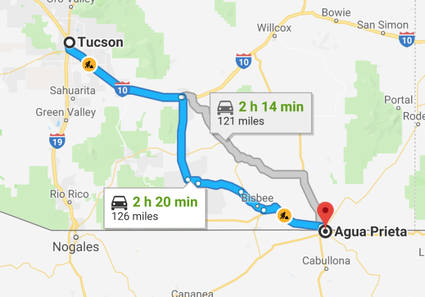

When I first contemplated how I would format my blog post about the Border Delegation, I thought that I would title it, “Hurt and Hope,” and describe the ways in which I observed and experienced both throughout the week. I quickly realized, though, that sorting my experiences that way was too binary. Most of what I saw and learned encompassed hints of both hope and hurt. At church the Sunday after our Border Delegation concluded, Pastor Bart Smith spoke in his sermon about Emmanuel: God with us. He said that emmanuel is forever and ongoing. With it being the beginning of advent, he posed the question, “When is a good time for love to be born?” In my mind, I considered, “When is a good time to migrate?” Inspired by the sermon, I arrived at this title and framework: Emmanuel in the Borderlands. Emmanuel at Café Justo Daniel Cifuentes showing us different types of coffee beans that result in variations in flavor at the Café Justo roastery Daniel Cifuentes showing us different types of coffee beans that result in variations in flavor at the Café Justo roastery Café Justo (translated: fair or just coffee) is a coffee cooperative owned and operated by farmers in Chiapas, Mexico. The coffee is grown in Chiapas and roasted in Agua Prieta. It is sold in Mexico, the U.S., Canada, and France, mostly at churches. During our time in Agua Prieta, we were given a tour of the roasting facility and learned about their operations from Café Justo employees, Daniel and Adrián. Café Justo began in 2002 with a microloan from Frontera de Cristo. Many farmers from Chiapas were migrating to Northern Mexico or to the United States because the price of coffee fell so dramatically in the 1990s that they could no longer support themselves or their families. Community and family unity suffered greatly. In response to the economic and social crisis, Café Justo was formed as a way to cut out the middle man in the coffee growing and selling process so that the farmers in Chiapas could receive a fair price for their beans. In addition to being paid a fair price for the fruit of their labor, farmers who are part of the cooperative receive benefits, such as health insurance and retirement plans. Now, some of the original farmers are retiring, and their children are working as part of the co-op. The same families that would have been separated by migration as a result of environmental and economic factors out of their control, are now living and working intergenerationally and have the resources to invest in their community. When is a good time to migrate? Emmanuel in a Family’s Home Full disclosure: this is not an actual photo of the lentil soup that we ate, but it is a photo on Google that looks very similar. Full disclosure: this is not an actual photo of the lentil soup that we ate, but it is a photo on Google that looks very similar. One evening during our time in DouglaPrieta, we were welcomed into the home of a young family: Flor, Miguel, and their daughter, Aleyda. We were a group of 13 people, but our hosts were very hospitable and generous. Flor prepared a lentil soup that we garnished with cilantro, onions, and lime. She served us pitchers full of agua fresca- piña, my favorite! Most of the time we were there, Aleyda, who is five, was in a side room watching cartoons and coloring with her dad. She wore shiny bows in her hair, and produced a shy smile when we asked her questions. After enjoying la cena, Flor and Miguel spoke to us candidly about life on the border. Flor grew up in Agua Prieta; Miguel in Chiapas. Due to a lack of job opportunities over a decade ago, Miguel migrated to the U.S. He explained that during his time in the United States, he only left his home to go to work. He lived in constant fear of any interaction with law enforcement. One day, while on his way to work, the vehicle he was in was pulled over, I think for mechanical issues. Miguel was the only individual in the vehicle who did not have authorization to work, so he was taken to the immigrant detention facility in Florence, Arizona. (Some of my colleagues at the Florence Project provide legal services to individuals detained there). Miguel described his six months imprisoned there as difficult and ugly. I could see in his facial expressions and hear in his words that he had many painful memories of Florence. After six months of trying to obtain a work permit, but with no avail, Miguel decided to sign an order of deportation and return to Mexico. He ended up in Agua Prieta and applied for a job at a maquiladora, or factory. Flor was a new hire at the same maquiladora at that time. Also limited by economic opportunity, many Agua Prieta folks work at factories run by multinational cooperations that are located near the border due to lax labor and tax laws. Although Miguel annoyed Flor at first because he asked many questions during work orientation, they eventually became friends and are now married with a child. As a United Statesian, I often have had the perception that people in Mexico are miserable. Especially people who live near the border, I thought, must have terrible lives filled with violence and despair. That is the opposite of what I experienced in the home of Flor, Miguel, and Aleyda. They were hopeful. They were hospitable. They were healthy. They were happy. Miguel said, “We have problems, like all families do, but we are very content to live in this community.” When is a good time to migrate? When is a good time for a child to be born? Emmanuel at Operation StreamlineThe part of our week in which it was the most difficult to believe Emmanuel: God with us was when we observed Operation Streamline in Tucson. Operation Streamline is a two hour-long, mass federal prosecutorial hearing that occurs every afternoon. Each day 70 to 80 individuals are prosecuted for a misdemeanor or a felony, solely related to entering the country not at a port of entry. If an individual has only entered once, and has not been deported, they generally plead guilty to a misdemeanor and are then turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) where they will be detained for months before being deported or, if they are statistically lucky, released to live in the U.S. If an individual has a prior deportation on their record, they are prosecuted for a felony and a misdemeanor, but will usually plead guilty to the misdemeanor so the felony is dropped. They are sentenced to 30 to 180 days in federal prison, after which they will be turned over to ICE and spend several months in detention until being deported, or if EXTRA statistically lucky, released. Our group of 13 and another group of folks on a church/border education trip entered a massive federal court room and were seated in the back. Many attorneys sat in the jury box. All of the usual court personnel was there: a judge, a secretary, an interpreter, and many federal marshals. When the judge was ready to begin, a group of seven people wearing street clothes, handcuffs, ankle shackles, and chains around their waists came out from a side door, had headphones were placed on their ears (they could not do it themselves because of the handcuffs), and stood in front of the judge. Seven of the attorneys stepped down from the jury box and stood behind each defendant. The judge went down the line of people asking them to verify their names, read them their rights, asked if they wanted to waive their right to a trial, read them their charges, and asked for their plea. She would usually read the full text (for an example, the rights) to the first or second person in line. She would say, “Do you understand your rights as I just explained?” By the third, fourth, fifth, person in the order, she would just say, “Same question.” It was apparent that efficiency, not comprehension or justice, was the name of the game. After each defendant pleaded guilty to their charges, whether they really understood them or not, the group of seven would be escorted out, and another group of seven would be escorted in. This process was repeated about ten times. It was uncomfortable, sad, and shameful to watch people being treated like this, especially in a U.S. court room. It was very difficult to feel the presence of God in that room. Among the approximately 70 humans who we saw in chains standing in front of a judge who spoke to them in complex legal terminology in a foreign language, were a pregnant woman, indigenous language speakers whom the judge coerced into using the Spanish interpreter even if comprehension was limited, and boys who appeared and sounded to be 14 or 15 years old, but told the judge they were 18. One defendant broke out of the mechanical saying “Sí” to all of the judge’s questions, and decided to speak up when given the opportunity. I have contemplated his story several times over the last few weeks. Jorge was one of the individuals who had a prior deportation on his record, so he was being charged with a felony and sentenced to time in a federal prison. When the judge asked, “Do any of the defendants want to say anything?” Jorge bravely said yes. He approached the microphone and asked the judge if his sentence could be reduced. He explained that he is a single father, and his United States citizen daughter is in Mexico. The longer his prison sentence, the longer he would be separated from his daughter. It seemed like what he wanted was to quickly be deported so that he could return to caring and providing for her. The judge said, “I’m sorry to hear that, but I have no control over sentencing. It’s between your attorney and the government.” Jorge was sentenced to 180 days, six months, in a U.S. federal prison. When is a good time to migrate? Emmanuel at the Port of EntryDuring our time in Agua Prieta, we had the pleasure of sharing a meal with migrants who were temporarily living at a shelter on the Mexican side of the border. There was a variety of identities present at the shelter, called C.A.M.E. There were a couple of Honduran and Guatemalan families. There were three Mexican men who had spent the majority of their lives in the U.S. There was a group of Honduran transgender women. The C.A.M.E. volunteers and the migrants collaborated to prepare a delicious dinner, do dishes, and clean. We tried to wash our own dishes and sweep, but as their guests, they generously cleaned up after us. While we ate, we had the honor of hearing their stories, sharing in their pain, joking and laughing. Migrants are at this shelter, usually, waiting to cross into the United States. There is a small port of entry between Agua Prieta and Douglas. If a migrant sets foot on U.S. soil and expresses a desire to apply for asylum to a government official, U.S. and international law dictates that the person has the right to stay in the United States (often in detention) while fighting for asylum in immigration court. Entering the U.S. at a port of entry is the best way to do this because it is safer than crossing the desert or the Río Grande. It also carries less potential legal backlash than does entering not at a port of entry (see Operation Streamline, above). However, the number of people who can approach a port of entry and request asylum is limited. And, the number has been decreasing in recent months. (I discussed this phenomena in my post about El Paso.) The Agua Prieta/Douglas port of entry is small, but it has the capacity to process eight asylum seekers per day. In recent weeks, it has been processing maybe one or two people per day. So, some of the folks we met at C.A.M.E. were waiting to go to the port of entry and request asylum, but they had been turned away day after day. During our dinner at C.A.M.E., we met María. She wore her hair in a pony tail, and had a beautiful smile. María was traveling with her 13 year-old daughter, Julisa, who was wearing a blue shirt with white buttons when I met her. The morning following our shared dinner, María and Julisa were planning to go to the port of entry, bright and early, accompanied by C.A.M.E. volunteers. Before leaving that night, we wished them luck and safe travels. The next day we were busy with our scheduled programming. We spent most of the day in Agua Prieta, but around 4 pm, we were crossing the border to participate in a prayer vigil in Douglas. As we approached the port of entry, we saw María and Julisa. Sitting on the concrete. Waiting. They told us that they had been there since 7 a.m., but had not yet been allowed to set foot on U.S. soil to request asylum. We were in a hurry to get to the prayer vigil, so we did not talk for long. We pulled our U.S. passports out of our pockets and were in the U.S. within minutes. After the prayer vigil, some members of our group returned to the port of entry with food, coats, and sleeping bags for María and Julisa. Although they could have returned to C.A.M.E. for the night, they decided to sleep on the concrete in the cold because they didn’t want to “lose their place in line.” María was eight months pregnant, with bronchitis. When is a good time for a baby to be born? When is a good time to migrate? Where is Emmanuel?As we are now in advent, a time of preparation for the coming of Jesus, I am trying to identify Emmanuel in my life. I am trying to consider where God is with me. I experienced God in the faces and in the lives of Daniel, Adrián, Flor, Miguel, Aleyda, Jorge, María and Julisa. I experienced God in the many life-changing ministries of Frontera de Cristo. I experienced God in the DouglaPrieta community. I experienced God in the hope and in the hurt. As Pastor Bart said, Emmanuel is forever and ongoing.

When is a good time to migrate? When is a good time for a baby to be born? When is a good time for love to be born?  Source: Google Images Source: Google Images I work at BorderLinks leading educational trips or delegations that introduce people to the border and immigration issues. Groups come from colleges, graduate schools, seminaries, and churches across the country. During a delegation, participants meet with different immigration stakeholders such as immigrant-led political organizing groups, border patrol, and pastors involved in the sanctuary movement. In addition, participants learn about topics like NAFTA, Popular Education, border history, and the prison system in interactive workshops led by BorderLinks staff. Delegations are an intense whirlwind of complex ideas, personal stories, and strong emotions. Days are often long, challenging, and eye-opening. Participants leave broken-hearted, inspired, and determined to change our broken immigration system. I got back from winter vacation ready to lead my second delegation. I was excited, but nervous as it was the first delegation I would plan completely on my own. Reading my participants' applications, I felt uneasy. These students were very different from most people who I know and have grown up around. Most were from the midwest, studying criminal justice, and hoping to go into law enforcement. One of the male participants was planning on joining the Border Patrol after graduation. About half the group had never been outside of the country and most had not lived in multicultural settings. How would this group react to BorderLinks' liberal ideology? Would they feel comfortable in this immersive cultural environment? After meeting the group at the airport, I breathed a sign of relief. They were great. When I asked them to help put luggage on the roof rack they immediately organized as a team, volunteering to help. Driving back to the office, several of the group members talked about football and hunting. I chuckled, thinking about how different this was from my San Francisco upbringing. When we got into the office, one of the men asked me if there was something to drink. I responded, "There's only milk in the fridge." His face lit up as he said, "I love milk. I'm from Wisconsin." I smiled and thought, this'll be fun. As the week went on I got to know the participants better. Over meals, we cracked jokes and talked about our personal lives. Many of my participants work at least one job in addition to going to school full time. One of the women goes to school, works as a waitress, and works the night shift at a gas station (10 PM - 6 AM). She only sleeps a few hours from Sunday to Tuesday. I was amazed by my participants' work ethic and persistence. Many of them are first-generation college students, forging their own path. About halfway through the week, the participants stayed with host families in Tucson. These families are made of immigrants who are active in their community. BorderLinks routinely organizes home stays so participants can meet people who are directly affected by immigration issues. As I dropped off the participants, I noticed several were anxious as they had never done a home stay and they did not speak much Spanish. I assured them that all our home stay families are friendly, welcoming, and have hosted many students before. The next morning, I got up early to pick up students from home stay houses. While driving, I got call from the group leader notifying me of "a situation." The college president had found a student's Tweet (from Twitter) that said they had been "kicked out of their lodging, forced to live with illegals, and not allowed to call Homeland." My heart sank. Who wrote this? Did someone actually want to call Homeland Security on these immigrant families? Was someone going to call ICE? Comments like this on social media can be vague, unintentional and extremely hurtful. To me, this Tweet was a threat. My jaw clenched as I thought about the families who had generously and bravely opened their houses to these students. Where they now in danger? Had I put these people in harm's way? Hurt and panicked, I began to doubt the trust I had put in these students. After reconvening, I immediately sat the group down and explained the severity of inflammatory comments on social media. Also, I described what it would look like if someone called ICE on one of these families. Imagine flashing lights, crying children, not being able to contact your family for days, detention, an expensive bond, and a chance of being deported, separated from your home and family. Disappointed and perplexed, I looked out at the group for reactions. Most participants were shocked and apologetic as this Tweet did not reflect the majority's opinions or home stay experiences. In fact, the Tweet was not written by someone in the delegation, but by their friend who did not fully understand the context. Although I still felt violated, I breathed deeply, knowing that the Tweet should not be taken seriously. Yet, I reflected on why this may have happened. Many of my participants grew up in environments that have a high respect for cops and believe you should do your best to enforce the law whenever possible. As many are going into policing, they maybe experienced an internal conflict or cognitive dissonance when living with a person had immigrated illegally. Using this logic helped me understand my participants' perspectives, but did not shift my opinion that this Tweet was a callous, disrespectful display of entitlement and power. Although I dutifully follow most laws myself, I try to think critically about the law. I do not think that government-dictated rules necessarily have higher moral authority than personal or religious values. Even though laws are powerful, foundational structures that control our lives, they can be changed quickly with a politician's signature. In the last couple years, huge cultural concepts such as our legislative definition of marriage has changed. Laws are a flexible, impermanent cultural constructs. Mike Wilson, a member of the Tohono O'odham tribe in Arizona, is known for his controversial work distributing drinking water for passing migrants on the Tohono O'odham nation. Although, this is against his tribe's laws, he continues to do it because he believes the God's law is greater than any man-made law. If we truly loved our neighbor as ourselves, we would give them water. If we truly loved our neighbor as ourselves, we would help them through deadly terrain. If we truly loved our neighbor as ourselves, we would let them live in peace with their families. Acts 5:29: "But Peter and the apostles answered, 'We must obey God rather than men.'" Despite this negative moment during my delegation, the rest of the trip went well. The participants expressed a greater, more complex understanding of immigration policy, undocumented immigrants, and minority-police relations. One participant wrote, "The most impactful part for me was the home stay...being able to talk one-on-one with them really opened my eyes... This will inform my decisions in my career in law enforcement for my whole life." I thank this delegation for opening my eyes. They taught me more about police work, the military, and what it is like to live in a different part of the United States. I think we both shocked, challenged, and comforted one another. Most of all, we reminded each other to meet people where they are in their life journey without making hurtful comments or assumptions. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed